Britain is one of the most ecologically depleted nations on earth. We have lost all our large carnivores and most of our large herbivores. While the average European forest cover is 37%, ours is just 12%. Our ecosystems have almost ceased to function. Because of the absence of trees and loss of soil, our watersheds no longer hold back water, with rainfall flashing off the hills and causing flooding downstream. The latest State of Nature report reveals that 56% of species have declined over recent decades, and that more than 1 in 10 species are under threat of disappearing from our shores altogether.

Rewilding offers a chance to reverse that: a chance to bring nature back to life and restore the living systems on which we all depend. A chance to work with communities to restore to parts of Britain the wonder and enchantment of wild nature; to allow magnificent lost creatures to live here once more; and to provide people with some of the rich and raw experiences of which we have been deprived.

Rewilding is not a new idea. And it’s not just about bringing back wolves as the media might have you think. And it’s not about going back in time, but about going forward by embracing a realistic, resilient ecology. It can occur at a range of scales, from small-scale habitat restoration within cities, to the development of large-scale wild, and even wilderness, areas on land or at sea. What is common to all rewilding projects is a focus on process-led conservation – restoring natural processes, then standing back as much as possible - rather than any goal-orientated focus on the conservation of certain species or habitats.

This is not to suggest that rewilding seeks to ditch traditional nature conservation management. That approach often works, but it is clear that nature will not thrive if restricted to small reserves that are disconnected from each other and the natural systems that should support them. It’s clear that we need to move from a focus on protection of nature, to a system that promotes both protection and restoration of nature across landscapes and at sea.

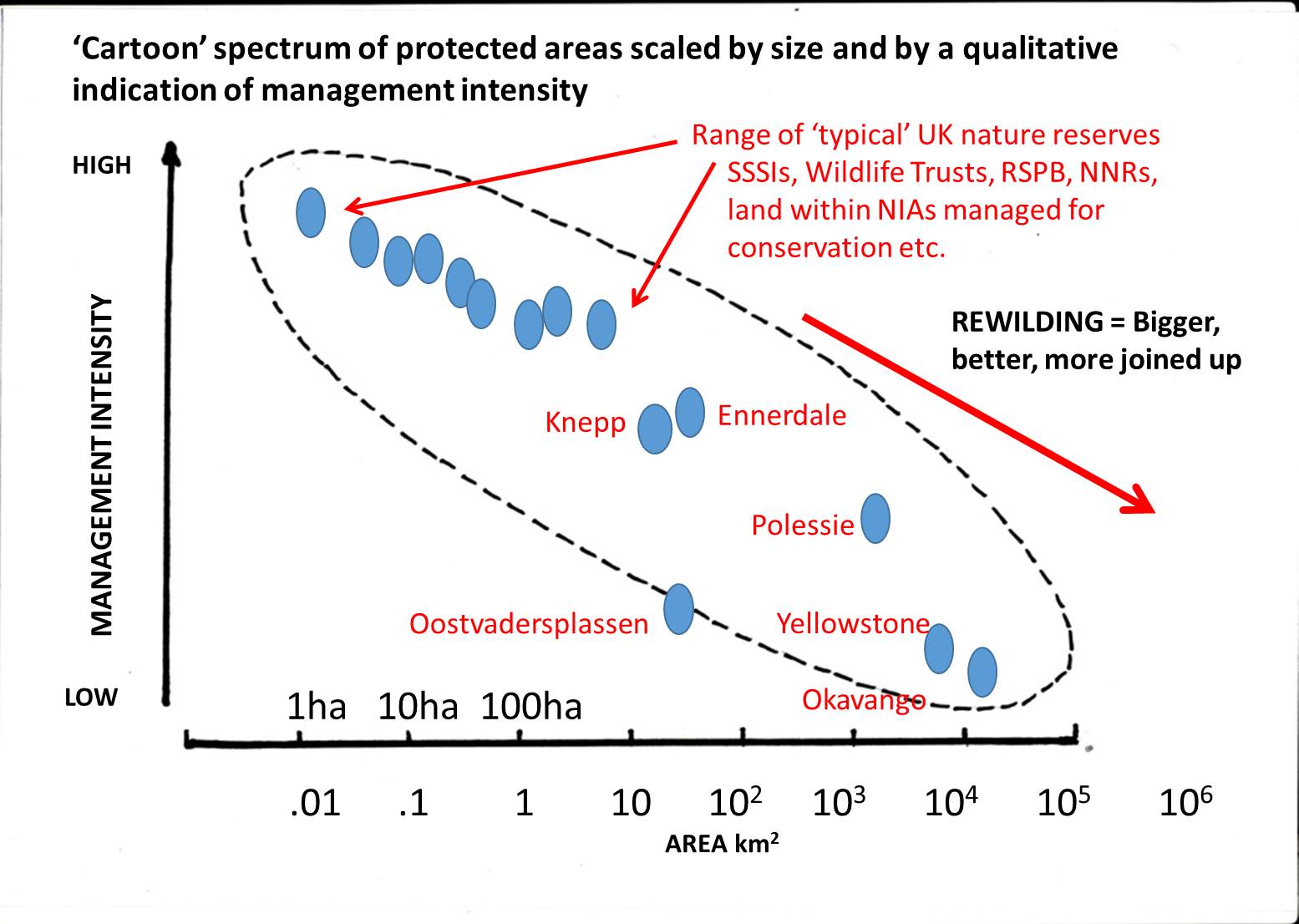

Rewilding is essentially an extension of the “Making Space for Nature” approach of “bigger, better, more joined up”. The slide below is borrowed from Sir John Lawton. He argues rewilding is about the process of moving conservation from the top left of this diagram towards the bottom right – about making space for nature at a larger scale, and reducing management intervention (and costs) as a result.

Graph Credit: Sir John Lawton (Feb 2016)

Rewilding can be transformative for nature, by increasing connectivity, creating diversity and making room for species to move through landscapes as they adapt to environmental change. It puts nature’s processes, structures and species back into our landscapes to enable them to become more self-sustaining, biologically richer and better able to support society and the economy.

The current policy framework largely works against rewilding. Farm subsidies through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) create a powerful incentive to prevent ecological restoration: wherever land ceases to be in ‘agricultural condition’ it is disqualified from payments. Conservation designations often insist that ecosystems are kept in a state of arrested development, and attempts to allow trees or missing animal species to return are usually deemed unlawful. Regulations around wild animals, livestock movement and species reintroduction can also be major impediments.

However, Defra’s forthcoming 25 Year Plan for the Environment and the development of a land management policy to replace CAP post-Brexit both provide excellent opportunities to advance and expand policy in relation to the natural environment. We are calling for a more progressive land management policy based on public payment for delivery of public benefit. This should reward farmers and land managers for the delivery of ecosystem restoration and associated benefits, such as improvement of water quality at source, natural flood risk management and carbon storage in soils and biomass.

We also believe that communities should be given a far greater role in environmental decision-making, informed by open data and expert facilitation. There are some great examples of projects involving communities in flood risk management. In Pickering, North Yorkshire, rather than building a £20 million concrete flood wall through the centre of town, the community planted 29 hectares of woodland upstream to naturally soak up water, and created hundreds of natural obstructions in the river made of logs, branches and heather to restore its natural flow. The flood risk has now fallen from 25%, to just 4%, and at a fraction of the cost of hard defences. Results of the scheme can be found on the Forestry Commission website.

Policy debate is also needed to support a more strategic approach to species reintroduction. The animals we lack, such as beavers, boar, lynx, and wolves, are not just ornaments of the ecosystem - they have a role as ecosystem engineers and are essential to an effectively functioning environment. They drive ecological processes and are crucial components of flourishing ecosystems. Yet the current approach to species reintroduction in England and Wales is rather piecemeal, with individual landowners and organisations making applications for localised reintroductions. We believe a national forum should be established to bring stakeholders together to discuss the potential benefits and disbenefits of different approaches. International experience has shown that stakeholder engagement plays a key role in the success of species reintroductions, which with the right planning and execution, they can benefit the species concerned, the wider biodiversity, local communities and the public as a whole.

The rewilding movement in Britain is in a design and innovation phase. We believe any new policy framework should embrace this, and create tax incentives and innovation funding to support the development of new nature-based economic models for land use in different regions and at a range of scales.

We hope rewilding will both inspire and revitalise communities across Britain, by offering a positive environmental vision and by bringing in new sources of income and jobs. Examples from around Europe show that this offers a great potential for the recovery of the human economy as well as the natural world.

Helen Meech joined Rewilding Britain as Director in September 2015. Helen has worked in the natural environment policy and campaigns sector for the last 10 years, most recently leading the National Trust’s public engagement on nature, including the award-winning 50 things to do before you’re 11 3/4 campaign.