I have had a fascination with islands for more than 50 years. I lived in Jamaica from when I was five until I was ten and when I was not observing the local wildlife, avidly read Treasure Island and stories about the Spanish Main. My love of islands undoubtedly stems from these early experiences. As I grew older I was influenced by Darwin and his epic voyage on the Beagle, and his appreciation of the island fauna and flora he encountered. As an undergraduate, I fell in love with the concept of island biogeography as exemplified by McArthur and Wilson’s great little book (McArthur & Wilson, 1967) and the classic island defaunation experiment of Simberloff & Wilson (1969, 1970). So what has this to do with roundabouts I hear you asking?

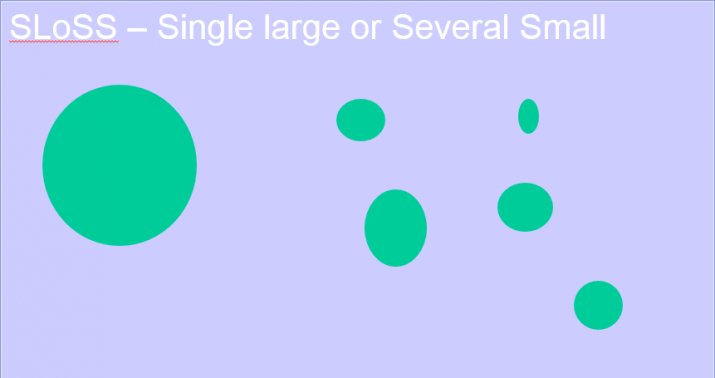

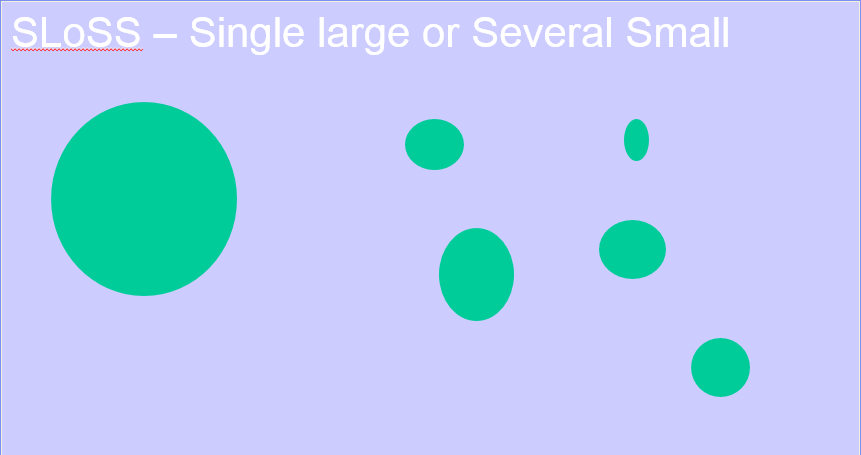

For many years I taught a final year course at Imperial College London, in Applied Ecology. Part of the course involved talking about island biogeography and species-area relationships and how this related conservation and reserve design and this of course involved talking about the SLoSS debate (Higgs & Usher, 1980; Quinn & Hastings, 1987; Murphy, 1989), see Figure 1 below for meaning. Fed up with the misconception that students and others have, that conservation is entirely focused around the large charismatic mega-fauna and exotic tropical locations, I wanted to talk about things closer to home and more relevant to my students and their future careers. Although my undergraduate teaching was based in South Kensington, my office was at the Silwood Park campus, near Ascot and I lived in Bracknell, some 10 km away. To get to work every day, I had to negotiate thirteen roundabouts of varying sizes and appearance and it suddenly struck me that here was a perfect way to talk about urban ecology, island biogeography and nature conservation and to introduce students to practical research which might actually lead on to a career in ecology or nature conservation.

Figure 1: SLOSS: Single Large Or Several Small

I approached Bracknell Forest Borough Council with a certain degree of trepidation, but they were remarkably laid back about the whole things just insisting on us attending a Health & Safety briefing, to wear high visibility jackets and to have surveying signs posted at the entrances and exits to the roundabouts. We then designed a sampling programme which eventually involved sampling twenty-three roundabouts in Bracknell. We used pitfall trapping, tree beating and foliage sampling, suction sampling, point transects and vegetation surveys, thus covering epigeal insects, tree dwelling insects, grassland hemiptera, bees, butterflies and even birds, together with a measure of habitat diversity and vegetation cover. We asked four simple questions:

1) Do urban green spaces act as biogeographical islands?

2) Are urban green spaces significant reservoirs of biodiversity?

3) Can management practices improve the biodiversity on these urban green spaces? and

4) is there a conservation role for urban green spaces?

The study which ended in 2012, lasted for twelve years, and as well as involving the original undergraduates, provided research projects for a number of BSc and MSc students and even one for a PhD student. So what did we find? The data are still not all published but it will perhaps come as no surprise that we found a lot of insect species, but what may surprise you is how many species all together. We only sampled about 8 ha of green space but we found 54 species of carabid beetle (15% of the British list), 187 species of bug (4.5 % of the British list) and 44 species of bird (7.6 % of the British list). These are remarkable figures, especially when you consider that the Silwood Park campus where my office was based, covers 110 ha of mixed woodland, grasslands and includes a lake, but only hosts 56 species of bird year round (or 74 species if you count migrants). We only sampled a fraction of Bracknell’s green spaces, if we had sampled more we would almost certainly have found mores species of insects and birds. Wes estimated for example, that Bracknell probably hosts 20% of the British list of Hemiptera (Helden & Leather, 2005).

To return to the original point of the pedagogical exercise, the four questions we set out to answer. First, yes for beetles, birds, and bugs, roundabouts do act as biogeographical islands and we were able to demonstrate significant species-area and area-abundance relationships, i.e. the bigger the islands (roundabouts) the greater the number of different species we found and the more individuals of each species were found (Helden & Leather, 2004; Leather & Helden, 2005a), second, we definitely showed that the roundabouts were significant reservoirs of biodiversity (Leather & Helden, 2005b) and that management, either through reduced mowing (Leather & Helden, 2005b) or by increased planting of native species (Helden et al., 2012) would result in enhanced biodiversity. Finally, although we would never dare to compare the roundabouts of Bracknell with the Amazonian rain forest, there is undoubtedly a conservation role for them and similar urban green spaces, we found several notable species of Hemiptera (Helden & Leather, 2005).

So, next time you are waiting to enter a roundabout, don’t just think of it as an impediment (or aid) to your journey, but as a haven of wild-life, an urban nature reserve or even as a work of art, especially if you are in France.

Figure 1 (above): A roundabout in Bracknall

References

Helden, A.J. & Leather, S.R. (2004) Biodiversity on urban roundabouts - Hemiptera, management and the species-area relationship. Basic and Applied Ecology, 5, 367-377.

Helden, A.J. & Leather, S.R. (2005) The Hemiptera of Bracknell as an example of biodiversity within an urban environment. British Journal of Entomology & Natural History, 18, 233-252.

Helden, A.J., Stamp, G.C., & Leather, S.R. (2012) Urban biodiversity: comparison of insect assembalges on native and non-native trees. . Urban Ecosystems, 15, 611-624.

Higgs, A.J. & Usher, M.B. (1980) Should nature reserves be large or small? Nature, 285, 568-569.

Leather, S.R. & Helden, A.J. (2005a) Magic roundabouts? Teaching conservation in schools and universities. Journal of Biological Education, 39, 102-107.

Leather, S.R. & Helden, A.J. (2005b) Roundabouts: our neglected nature reserves? Biologist, 52, 102-106.

McArthur, R.H. & Wilson, E.O. (1967) The Theory of Island Biogeography, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA

Murphy, D.D. (1989) Conservation and confusion: wrong species, wrong scale, wrong conclusions. Conservation Biology, 3, 82-84.

Quinn, J.F. & Hastings, A. (1987) Extinction in subdivided habitats. Conservation Biology, 1, 198-208.

Simberloff, D. & Wilson, E.O. (1969) Experimental zoogeography of islands: the colonization of empty islands. Ecology, 50, 278-296.

Simberloff, D. & Wilson, E.O. (1970) Experimental zoogeography of islands: a two-year record of colonization. Ecology, 51, 934-937.