In this article IALE UK postgrad and early career rep Caitlin Lewis tells us about a recent research trip to Belgium and shares how to look for similar opportunities.

“How did I end up here?” I wondered as I gazed out of the car window at some of Europe’s tallest beech trees.

As we bounced up the steep, bumpy road, I looked out in awe at the wooded landscape, known among the ecology community in Belgium for its high volume of deadwood and rich biodiversity.

We were driving through the Sonian Forest (Zoniënwoud), a >4400 ha forest that spans across the three regions of Belgium; Brussels, Flanders and Wallonia. Many Belgian forests were subject to extensive deforestation during the Napoleonic Wars but parts of the Zoniënwoud remained untouched and are now encompassed in the “Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe” UNESCO World Heritage Site.

We came to a halt and I jumped out to look up at the distant canopies of these spectacular trees. The harvested parts of Zoniënwoud and other areas of Belgium were typically replanted with beech, including the looming giants before me, which were planted in 1909. No one is entirely sure why the beeches in Zoniënwoud grew so tall, my host explained. Considering the compacted soil from the use of wagons in the area in the past centuries, and the shallow-rooting nature of beech, the beech trees in Zoniënwoud defy known logic (see left hand image above).

Long-term forest monitoring in Flanders, Belgium

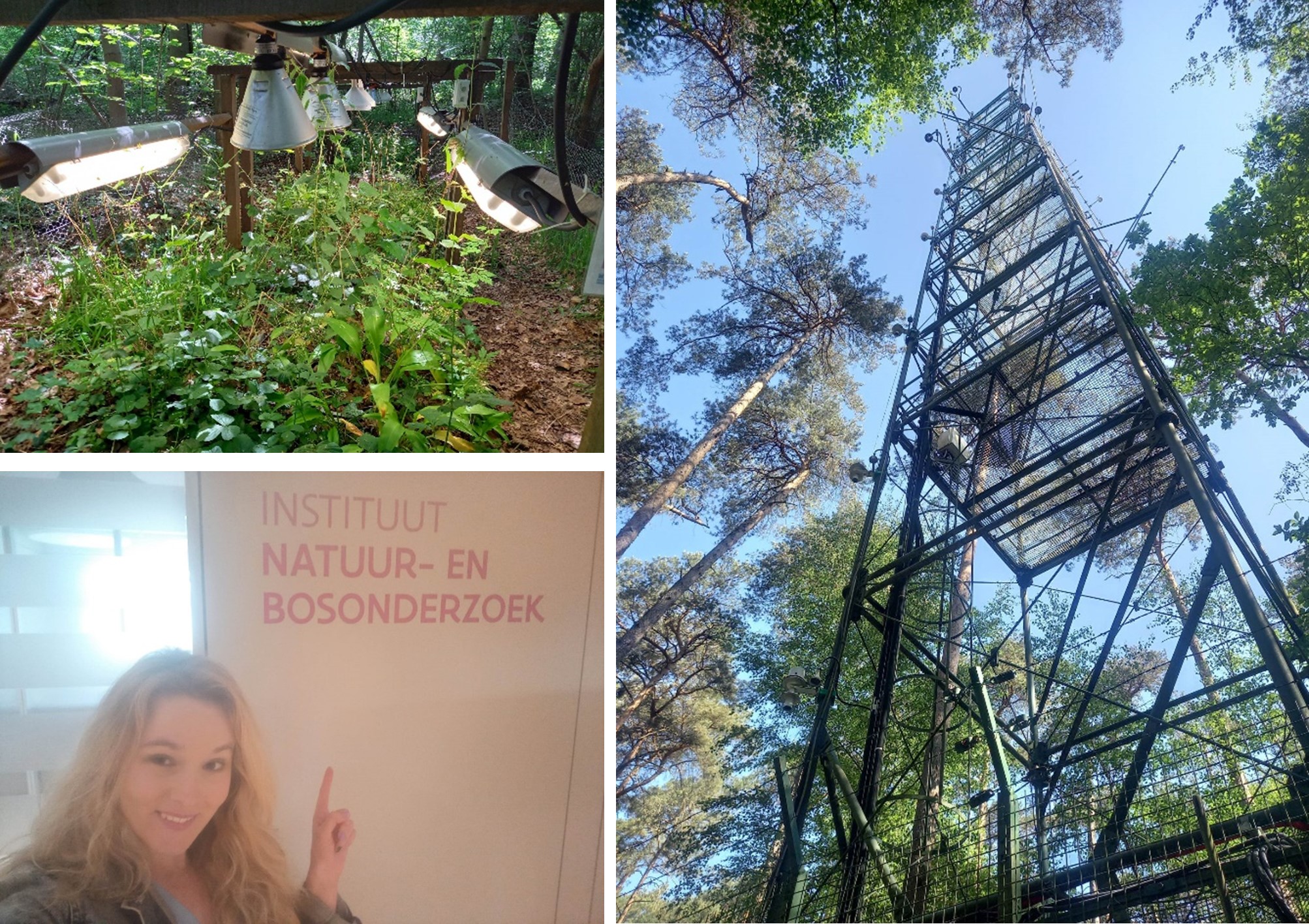

Rightmost three pictures, above, show: (top left) soil lysimeters installed at Zoniënwoud, (bottom left) sapling regeneration in a vegetation monitoring area in Zoniënwoud, (right) a stemflow collector installed on a beech tree, connected to several large storage containers, situated next to a throughfall collector mounted in a cylinder.

A little set back from the forestry track we arrive at our intended destination- a research site. At Zoniënwoud, lysimeters collect soil solution from three layers of the soil, funnels mounted one meter above the ground collect the water that falls through the forest canopy (throughfall), and mesh bags staked to three posts collect litterfall. Some trees were fitted with a cut-in-half pipe connected to five large containers, to collect water flowing down the trunk (stemflow). Whilst stemflow contributes to an insignificant portion (1-2 %) of water entering the soil in the coniferous forests we had visited the previous day in Brasschaat and Ravels, stemflow can contribute ~10 % of water entering the soil in beech forests. In a heavy rainfall event, the large stemflow containers can end up overflowing whilst the throughfall collectors catch little water.

After an explanation of the equipment, we made our way out of the trees, wading through a tangle of saplings regenerating from the ground. Another mystery of Zoniënwoud; less than two decades ago there was no beech regeneration at this site but since approximately seven years ago there has been regeneration every year. Perhaps a result of declining nitrogen deposition inputs, my host hypothesised. Zoniënwoud is near an airport and the dense traffic network of Brussels, and was chronically exposed to elevated NOx deposition, although a slight decline in NOx pollution between 1994-2010 was observed.

Zoniënwoud is one of five long-term monitoring sites in Flanders designated as a Level II site for the International Co-operative Programme on Assessment and Monitoring of Air Pollution Effects on Forests (ICP Forests). During my week in Belgium, we also visited three other ICP Forest sites. Some were associated with other research projects too. The Scots pine site in Brasschaat had a flux tower installed as part of the Integrated Carbon Observation System (ICOS) network. The other beech site we visited in Gontrode is also used by Ghent University for research and teaching. QR codes were attached to some trees outside the Level II area which linked to webpages providing information and visualisations of the data collected at the side. Several trees were fitted with dendrometers and sap flow meters, and a large long-term manipulation experiment investigating interactions between light availability, nitrogen inputs and woodland ground vegetation cover.

ICP Forests and the new CLEANFOREST COST Action

ICP Forests is a European-wide network of forest sites where several variables connected to forest condition and effects of air pollution are measured according to standardised protocols. The programme began in 1985. Its Level I network provides data on how forest condition varies geographically over time in response to air pollution, whereas the Level II network is more detailed, measuring more variables to understand cause-effect relationships between forest condition and stressors.

The UK has several Level II sites, managed by Forest Research. During my PhD, I have used data collected at the UK Level II site, Thetford Forest in East Anglia, modelling-based research, and I am also using the European Level II database to investigate former land use impacts on soil nitrate leaching fluxes. It is the latter task that brought me to Belgium. Through a new COST Action initiative, CLEANFOREST, I was granted funding to undertake a short-term scientific mission (STSM), which allowed me to visit Dr Arne Verstraeten at the Institute for Nature and Forests, Belgium. CLEANFOREST intends to connect researchers involved in several different forest-related long-term monitoring networks and manipulation experiments in Europe together, including ICP Forests, ICOS and eLTER, and connect researchers to forestry practitioners and policy makers.

Getting involved in COST Actions

The European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) is an EU-supported organisation that funds interdisciplinary research networks called COST Actions. The focus is to bring researchers and other professionals, from across Europe and beyond, together to form collaborations. The funds available through a COST Action are not intended to support direct research costs, but are intended to fund activities that foster networking and collaboration, such as Short-Term Scientific Missions, Training Schools, workshops, and annual meetings and conferences. To find Actions relevant to you, there is a list to browse here. Some notable actions for ecologists include SMILES, 3DForEcoTech, DSS4ES, EUFLYNET, MARGISTAR, ROOT-BENEFIT and BeSafeBeeHoney.

Individuals can get involved with COST Actions through the activities they run and/or can apply to join a working group. A working group is a group within a COST Action that focuses on a more specific topic and works on delivering the Action’s objectives through activities such as producing literature reviews and reports and aggregating databases together.

When I wrote my STSM application, I already had an idea in mind of a small project to work on closely related to my work and to the Action, and approached a researcher who had worked with one of my co-supervisors previously. However, through the network created by an Action, it is easier to approach researchers outside of your personal network. The maximum funding that can be granted through an STSM can support an international visit of a maximum of approximately four weeks, so can only support a small research project, but also consider that the focus of STSM’s is also to develop networks and facilitate training and knowledge exchange. When developing a STSM project, think about the technical skills you could learn from your host, opportunities for field work, chances to work with existing data, and how your activities could make a small contribution to the objectives of an Action.

The aim of my week in Belgium was to receive training on processing the European Level II database, which has helped me to analyse the data I need for a chapter of my thesis, and also to have the opportunity to visit Level II sites to learn about the research activities ongoing in these locations. At the end of June 2023, I will be starting a position at Forest Research managing the UK Level II database, so this STSM took place at the perfect time. I hope you are able to find opportunities to support your career development, but do get in touch if you have any questions: students@iale.uk

Acknowledgements: I am very grateful for the opportunity and would like to thank my host, Arne Verstraeten at the Institute for Nature and Forests, and my co-supervisor who helped me to get involved in CLEANFOREST, Elena Vanguelova, Forest Research.

Below: (top left) the Ghent University experiment investigating interactions between light availability, nitrogen inputs and woodland ground vegetation cover, (bottom left) me in the offices of the Institute for Nature and Forests to work on data processing, (right) an ICOS flux tower installed in Brascchaat.