Chris Foster is a lecturer in Animal Ecology at the University of Reading and a member of the ialeUK committee.

Original article: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11252-020-00997-1

The ecological importance of dung beetles is increasingly well understood. However – perhaps understandably given their perceived association with large herbivores – this charming group of insects has received little attention to date from urban ecologists. In 2015, a group of us at the University of Reading set out to understand how the varied urban landscapes of our town influence the community of beetles that are attracted to dung.

We know that dung beetles occur in urban greenspaces, including the University of Reading campus, where we have often recorded some of the commoner species in the Aphodius complex. These can breed in alternative sources of decomposing vegetation (such as compost heaps) as well as dung. We’ve also found members of the spectacularly beautiful genus Onthophagus attracted to traps baited with rotting chicken – beetle surveying can require a strong stomach!

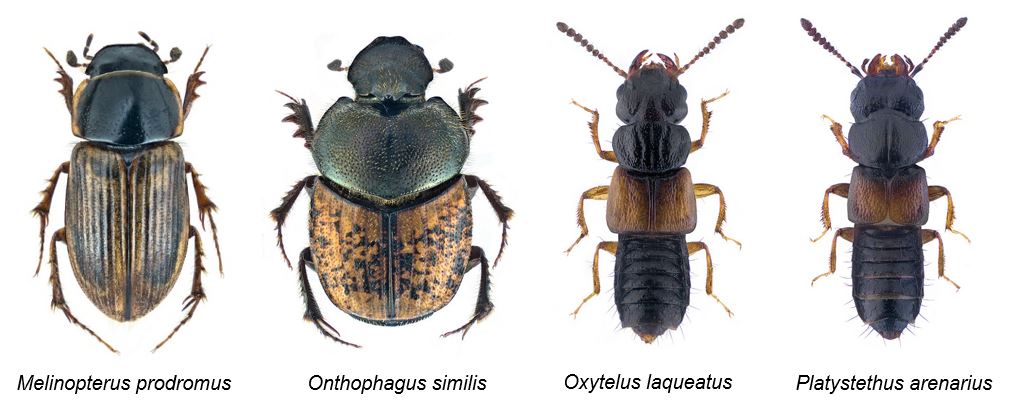

dung beetles. Oxytelus and Platystethus belong to the rove beetles, Staphylinidae, members of which are very common in dung.

Images by Udo Schmidt used under Creative Commons License CC BY-SA 2.0.

Nonetheless, it seemed reasonable to hypothesise that, with no livestock in the vicinity and few large wild mammals, some specialist species would suffer from a lack of dung availability and be scarcer in town. To unpick this and other elements of potential community modification, we asked whether dung-attracted beetles were i) more abundant or ii) more speciose at sites away from the urban centre, iii) if beetles in urban sites were on average smaller than at rural sites (in other groups of beetles, urbanisation has been found to filter out larger species) and iv) whether the community composition was modified by the level of urbanisation.

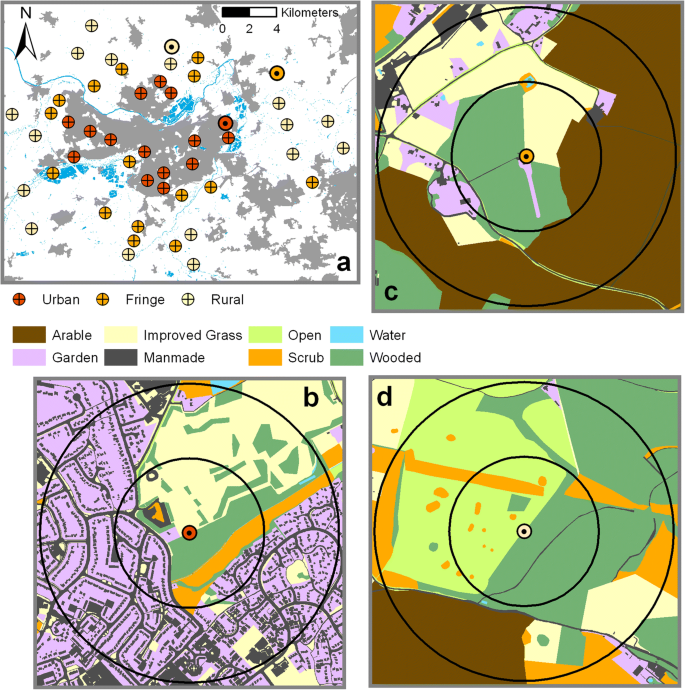

As some dung-associated species are predators that predominately feed on the larvae of other species and might occur in other prey-rich habitats, we also assessed these questions separately for predators and saprophagous species (which feed on decaying organic material). Finally, we explored the effect of landscape heterogeneity on beetle community composition to identify the key landscape elements driving any patterns identified. Dung-attracted beetles were sampled at 48 green spaces in the vicinity of Reading, categorised into three site types depending on their distance from urban areas greater than 10 ha.

So, was it a case of ‘crap towns’ for dung beetles? As we expected, the larger-bodied dung beetles were scarcer in the urban sites and most common in the more rural sites. But the species community was not particularly dissimilar between sites, suggesting that the urban species mix represented a subset of the wider species pool found in surrounding agricultural landscapes, rather than a novel assemblage of species. In fact, several urban sites had a very similar species composition to some of the rural sites, while the overall abundance and species richness was not lower. It appears that high-quality urban green spaces can host a rich diversity of coprophilous beetle species, although the general trend emerging from the community analysis was still one of a shift along the urban gradient from larger specialist species to smaller generalists.

Species richness among predatory species was lower at urban sites, but only by an average of one fewer active species compared to rural sites, and this difference only appeared during the earlier surveys. Some larger-bodied predators showed a preference for areas of the peri-urban landscape with large water bodies and patches of scrub, while the highest counts of the dominant species in our samples – two small predatory rove beetles in the genus Anotylus – were obtained in urban green spaces. So, while it isn’t exactly a dreamscape for dung beetles, some corners of Reading clearly have something to offer the discerning coprophile. It is also interesting to consider our results in the context of the functioning of urban ecosystems. Other recent research suggests that urban dung beetles are at last starting to get some attention, including in the tropics – an encouraging recognition of the key role they can play in decomposition and therefore ecosystem function.